U wilt een rondleiding door de omgeving van Mons naar aanleiding van de gebeurtenissen in de Oorlog 1914-1918?

Op speciale aanvraag is dit mogelijk, doch, dit is de enige rondleiding zonder Grappen en Grollen. Bezoek aan Militaire bezienswaardigheden, Fields of Honour... Groepen zijn beperkt tot 4-6 mensen.

Ik heb deze pagina in het Engels gedaan uit respect voor de Engelstalige bezoekers uit landen waar het meerendeel van de gesneuvelde militairen vandaan kwamen

Uw persoonlijke begeleider in Mons staat voor U klaar, wij doen alles voor de lol, wij zijn "Grap en Grol"

3rd Canadian Infantry_Divisionpatch

De Website Voor Mons

"Liberation of Mons 1918"

Een uitvoering zonder "Grap en Grol"

English;

We do understand that our English speaking visitors would like to know more. This is possible. You can contact us by e-mail at info@mons2016.com. Please be advised, if you want a "Official Tour" please contact the Mons Tourist Office. We are locals and take people on tour for a gift, a smile, a "Thank you". Of course we feel we do a better job, personal approach, well spoken English, we take our time and adapt to you.

Anything is possible according to your schedule, but please send an e-mail with you phone contact/number. We will do more in English, but again, we're just locals trying to show our beautiful city.

Americans, UK residents, Canadians, all is possible.

Deutsch;

Ich werde bald es auch auf Deutsch schreiben aus repekt fur die Deutsche Soladaten und ihren Gräber. Sie können mir immer contaktieren bei e-mail info@mons2016.com

Battle of Amiens

The allied command had developed an understanding that the Germans had learned to suspect and prepare for an attack when they found the Canadian Corps moved in and massed on a new sector of the front lines. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George reflected this attitude when he wrote in his memoirs: “Whenever the Germans found the Canadian Corps coming into the line they prepared for the worst.”

A deception operation was devised to conceal and misrepresent the Canadians position in the front. A detachment from the Corps of two infantry battalions, a wireless unit and a casualty clearing station had been sent to the front near Ypres to bluff the Germans that the entire Corps was moving north to Flanders. Meanwhile, the majority of the Canadian Corps was marched to Amiens in secret. Allied commanders included the notice "Keep Your Mouth Shut" into orders issued to the men, and referred to the action as a "raid" rather than an "offensive".

To maintain secrecy, there was to be no pre-battle bombardment, only artillery fire immediately prior to the advance. The plan instead depended on large-scale use of tanks to achieve surprise, by avoiding a preliminary bombardment, a tactic successfully employed at the Battle of Hamel.

The battle began in dense fog at 4:20 am on 8 August 1918.[7] Under Rawlinson's Fourth Army, the British III Corps attacked north of the Somme, the Australian Corps to the south of the river in the centre of Fourth Army's front, and the Canadian Corps to the south of the Australians. The French 1st Army under General Debeney opened its preliminary bombardment at the same time, and began its advance 45 minutes later. The operation was supported by more than 500 tanks, which helped to cut through the numerous barbed wire defences employed by the Germans.

The first day of the attack, August 8, saw the attacking forces broke through the German lines in dramatic fashion, with the Canadians pushing as far as 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) from their starting points. In many places the fog provided good cover for their advances in and through the furrows of the valley of the Luce river which ran through the centre of the Canadian's portion of the battlefield. The tanks were very successful in this battle, as they attacked German rear positions, creating panic and confusion. The swift advance led to a rapidly spreading collapse in German morale that ultimately led Erich Ludendorff to dub it "the Black Day of the German Army" when he was told of the psychological impact on his men.

Continuing to press the advantage gained on Day One, the advance continued for three more days but without the spectacular results of August 8, since the rapid advance outran the supporting artillery that could not be repositioned as quickly as the infantry advanced. By the 10th of August, the Germans had been forced to pull out of the salient that they had managed to occupy during Operation Michael in March, back towards the Hindenburg Line.

Left without an enemy to fight or a plan to pursue the retreat the Allied advances in the Amiens sector including those of the Canadians petered out by 13 August and the Amiens operation was halted.

The Canadians remained on the scene at Amiens until 22 August, consolidating their gains and prepared to defend against counter-attack. On the 23rd they were summoned to pull out and go into the line east of Arras for an attack that was to commence three days later. There they were stationed in the villages of Fouquescourt, Maucourt, Chilly and Hallu from which they would attack eastward toward the Hindenburg Line.

At Amiens the four Canadian Divisions faced and defeated or put to flight ten full German Divisions and elements of five others that sat astride their boundaries with the Australians and French on either side of them. In the five earnest days of fighting between the 8th and 13th of August the Canadian Corps captured 9,131 prisoners, 190 artillery pieces, and over 1,000 machine guns and trench mortars. The deepest extent of penetration from their jumping off points was approximately 14 miles or 22.5 kilometres, and in total the Canadians liberated an area of more than 67 square miles/173.5 square kilometres which contained 27 towns and villages.[14]

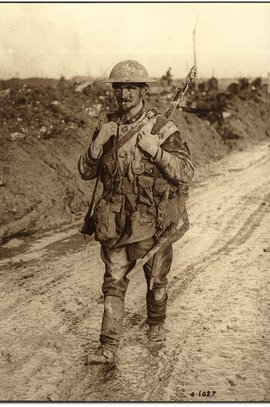

Canadian Troops on the Grande Place Mons, 15 August 1918

Rare Pictures Mons Grande Place 11 November 1918. Private Collection;

Copyright "Grap en Grol" HWMS

Breaking the Hindenburg Line

In Arras, the Canadians attacked eastward, smashing the outer defence lines near the powerful Drocourt-Quéant Line (the Wotan Stellung section of the Hindenburg line), along the Arras-Cambrai road. On September 2, 1918, the Canadian Corps, smashed the Drocourt-Quéant line, and broke its main support position, taking 5622 casualties, which brought the total losses of the Arras-Cambrai operation up to 11,423 casualties. After this, the Germans retreated across the Canal du Nord, which was almost completely flooded.

At the Battle of the Canal du Nord, following up the first breaking of the Hindenburg line, the Canadians used a complex manoeuvre to attack along the side of the canal through an unfinished dry section. The Canadians built bridges and crossed the canal at night, surprising the Germans with an attack in the morning. This proved the ability of Canadian engineers to construct new roads to cross the canal efficiently without the Germans noticing. The specialisation of troops and formally organised battalions of combat engineers was also effective as it allowed the soldiers to rest instead of working every day that they were not actively attacking. The Canadians then broke the Hindenburg line a second time, this time during the Battle of Cambrai, which (along with the Australian, British and American break further south at the Battle of St. Quentin Canal) resulted in a collapse of German morale.

This collapse forced the German High Command to accept that the war had to be ended. The evidence of failing German morale also convinced many Allied commanders and political leaders that the war could be ended in 1918. (Previously, all efforts had been concentrated on building up forces to mount a decisive attack in 1919.)

Pursuit to Mons

As the war neared its end, the Canadian Corps pressed on towards Germany and the final phase of the war for the Canadians was known as the 'Pursuit to Mons'. It was during these final thirty-two days of the war that the Canadians engaged the retreating Germans over about seventy kilometres in a running series of battles at Denain and Valenciennes in France and finally Mons in Belgium where they pushed the Germans out of the town on November 10–11. Mons was, ironically, where the British had engaged the German armies for the first time in battle in the Great War on August 23, 1914. As such, Mons is considered by some to be considered the place where the war both began and ended for the British Empire.

Canadian Red Ensign

For the citizens of Mons, it seemed like the horrors of The Great War would never end. Since the German occupation endless years earlier in 1914, their lives had changed forever.

For the youngest, their memories were only of bombs and artillery shells shaking their beds and making their homes fall down around them. They dreamed of tanks and guns, and of strange men in uniforms walking through their streets. They knew the smell of death better than the smell of baking bread.

For the older Belgians, their memories were of a time long-since passed... a time of peace that seemed a lifetime away... a time they feared they might never see again. Yet they lived in hope.

The first glimmer of hope arrived just after Easter in 1917 when they learned the Canadians had successfully taken Vimy Ridge. About 80 kilometres (50 miles) west of Mons, the Ridge had been occupied by the Germans in September of 1914. Rising over 130 metres (426 feet) above the surrounding land, it offered an unobscured view of all activities below. It was protected by many kilometres of trenches, underground tunnels, and impenetrable walls of barbed wire. Concrete bunkers sheltering machine guns were constructed on top. Vimy Ridge became a virtually impregnable fortress.

Every Allied attempt to take Vimy had failed, but the Ridge was crucial to the Allies if they wished to win the War. The challenge was finally handed to the Canadians. In every battle they waged, the Canadian forces had been victorious, even against impossible odds. Certainly nothing seemed more impossible than conquering Vimy.

Arthur Currie was not a soldier by nature. He was, in fact, a British Columbia realtor. But when the approach of war caused real estate to collapse, Currie joined the Canadian militia, and then devoured every book on military strategy he could find. As a result he was quickly promoted through the ranks, and, by 1917, he was Commander of the First Canadian Division. The burden of capturing Vimy Ridge from the German armies now fell on his shoulders.

When Currie studied the past attempts at taking Vimy Ridge, he was convinced they had all been doomed to failure before they began. A completely new approach was needed - something totally unexpected. Vimy Ridge was impregnable, but he was determined to find a way to break it.

Currie ordered intensive surveillance photos to be taken of the Ridge and all the surrounding land. These photos were then compiled into one large image of the entire area. For the first time in military history, detailed maps were made and distributed to every soldier. Meanwhile, with the help of the Allies, an exact replica of the Ridge, complete with tunnels, trenches and caves, was constructed behind the Front. There, Currie trained his men. After two months of intense training, the Canadians knew the Ridge as well as the Germans. Each man knew exactly where to go and precisely what he would find when he got there.

On April 9, 1917, at 5:30 AM, the assault began. It was daring and risky, and the Allied commands could only watch in amazement as events unfolded. Arthur Currie’s unusual offensive left the enemy scratching their heads in wonder. Instead of being bombarded by artillery as they expected, the shells fell in a solid line far across the land below. The attackers appeared either very inept or extremely cunning. At predetermined times, the bombardment advanced 100 metres toward the ridge, and behind it, with carefully-paced steps, advanced the Canadians in what would be named the Vimy Glide. Every three minutes the army moved steadily forward, 100 metres at a time, shielded by the ever-advancing artillery fire.

The advance moved forward through all the barriers, and incessantly up Vimy Ridge. Bodies lay where they fell. They would have to wait for the stretcher-bearers and medics following behind. The advance must continue, and it did. When it was over, Vimy Ridge belonged to the Allies for the first time since the beginning of the War.

3,598 Canadian soldiers died that day, and 7,004 more were wounded, but this victory marked the ‘beginning of the end.’ For his efforts, General Arthur Currie was knighted by King George V on the Vimy battlefield and named Commander-in-Chief of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Canadians were finally no-longer considered simply colonials or subordinates. For the first time, they were now regarded as full Allies.

While the Germans regrouped, the Allies began forming their final offensive to liberate all of France and Belgium.

August 4 to November 11, 1918, became known as Canada's Hundred Days. Flanked by Australian and French troops, the Canadian 'spearhead' advanced steadily eastward from Amiens (north-east of Paris) through France and into Belgium. Realizing defeat was imminent, the German High Command was devastated.

The advance continued incessantly. Losses were heavy on both sides, but in the end, freedom for the beleaguered French and Belgians lay in the wake of the terrible battles and bloodshed. Finally, in the early-morning hours of November 11, Canadian troops marched into Mons. The words of Victor Maistrau, Bourgmestre (Mayor) of Mons, describe that moment:

"At five in the morning of the 11th, I saw the shadow of a man and the gleam of a bayonet advancing stealthily along that farther wall, near the Caf´ des Princes. Then another shadow, and another. They crept across the square, keeping very low, and dashed north toward the German lines.

"I knew this was liberation. Then, above the roar of artillery, I heard music, beautiful music. It was as though the Angels of Mons were playing. And then I recognized the song and the musician. Our carillonneur was playing "O Canada" by candlelight. This was the signal. The whole population rushed into the square, singing and dancing, although the battle still sounded half a mile away.

"In the city hall at six in the morning I met some Canadians and we drank a bottle of champagne together. We did not know that this was the end of the war.

"The dawn revealed a strange sight in the square. The Canadian troops, exhausted from their long offensive, lay sleeping on the cobblestones while all Mons danced around them."

That same morning, on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, the Armistice was signed. World War I, The Great War, was over.

Neil Simpson

Peterborough, Ontario